Counties of England

| Counties of England | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| Category | Counties | ||||

| Location | England | ||||

| Found in | Regions of England | ||||

| Created |

| ||||

| Possible types |

| ||||

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

|

|---|

The counties of England are a type of subdivision of England. Counties have been used as administrative areas in England since Anglo-Saxon times. There are three definitions of county in England: the 48 ceremonial counties used for the purposes of lieutenancy; the 84 metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties for local government;[a] and the 39 historic counties which were used for administration until 1974.[1]

The historic counties of England were mostly formed as shires or divisions of the earlier kingdoms, which gradually united by the 10th century to become England. The counties were initially used primarily for the administration of justice, overseen by a sheriff. They subsequently gained other roles, notably serving as constituencies and as areas for organising the militia, which was the responsibility of the lord-lieutenant. The county magistrates also gradually took on some administrative functions.

Elected county councils were created in 1889, taking over the administrative functions of the magistrates. The functions and territories of the counties have evolved since then, with significant amendments on several occasions, notably in 1889, 1965 and 1974.

Following the 1974 reforms, England (outside Greater London and the Isles of Scilly) had a two-tier structure of upper-tier county councils and lower-tier district councils, with each county being designated as either a metropolitan county or a non-metropolitan county. From 1995 onwards numerous unitary authorities have been established in the non-metropolitan counties, usually by creating a non-metropolitan county containing a single district and having one council perform both county and district functions. Since 1996 there have been two legal definitions of county: the counties as defined in local government legislation, and the counties for the purposes of lieutenancy (the latter being informally known as ceremonial counties).

The local government counties today cover England except for Greater London and the Isles of Scilly. There are six metropolitan counties and 78 non-metropolitan counties. Of the non-metropolitan counties, 21 are governed in a two-tier arrangement with an upper-tier county council and a number of lower-tier district councils, 56 are governed by a unitary authority performing both county and district functions, and one (Berkshire) is governed by six unitary authorities whilst remaining legally one county.

For the purposes of lieutenancy England (including Greater London and the Isles of Scilly) is divided into 48 counties, which are defined as groups of one or more local government counties.[b]

Counties are also frequently used for non-administrative purposes, including culture, tourism and sport, with many organisations, clubs and leagues being organised on a county basis. For the purpose of sorting and delivering mail, England was divided into postal counties until 1996; they were then abandoned by Royal Mail in favour of postcodes.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Most of the historic English counties were established between the 7th and 11th centuries.[2] Counties were initially used for the administration of justice and organisation of the militia, all overseen by a sheriff. The sheriff was usually appointed by the monarch but in some cases, known as the counties palatine, the right to appoint sheriffs rested elsewhere; for example with the Bishop of Durham for County Durham, and with the Earl of Chester for Cheshire.[3][4]

A county's magistrates sat four times a year as the quarter sessions. For more serious cases judges visited each county twice a year for the assizes. In some larger counties the practice arose of holding the quarter sessions separately for subdivisions of the county, including the Ridings of Yorkshire, the Parts of Lincolnshire and the Eastern and Western divisions of Sussex. The quarter sessions were also gradually given various civil functions, such as providing asylums, maintaining main roads and bridges, and the regulation of alehouses.[5]

When parliaments began to be called from the 13th century onwards, the counties formed part of the system for electing members of parliament. Certain towns and cities were parliamentary boroughs sending their own representatives, and the remainder of each county served as a county constituency, with the MPs for such constituencies being known as knights of the shire.[6]

From Tudor times onwards a lord-lieutenant was appointed to oversee the militia, taking some of the functions previously held by the sheriff.[7] Some larger towns and cities were made self-governing counties corporate, starting with London in c. 1132,[c] with the right to hold their own courts and appoint their own sheriffs. The counties corporate continued to be deemed part of the wider county for the purposes of lieutenancy, with the exception of London which had its own lieutenants. The Ridings of Yorkshire had their own lieutenants from 1660 onwards. Sometimes smaller counties shared either a sheriff or lieutenant; the same person was usually appointed to be lieutenant of both Cumberland and Westmorland until 1876, whilst Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire shared a sheriff until 1965.[9][10][11]

The counties' role as constituencies effectively ceased following the Reform Act 1832 and the associated Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832. Most counties were divided into smaller constituencies, with the group of constituencies within each county being termed the 'parliamentary county'.[12]

County boundaries were sometimes adjusted, for example by some of the Inclosure Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries.[13] County and other boundaries were not centrally recorded with any accuracy before the 19th century, but were instead known by local knowledge and custom. When the Ordnance Survey started producing large scale maps, they had to undertake extensive research with locals to establish where exactly the boundaries were. Boundaries were recorded by the Ordnance Survey gradually in a process which started in 1841 and was not fully completed until 1888.[14] Many counties had detached exclaves, away from the main body of the county. Most exclaves were eliminated by boundary adjustments under the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844.[15]

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 created poor law unions, which were defined as groups of parishes and frequently crossed county boundaries. Parishes were typically assigned to a union centred on a nearby town, whether or not that town was in the same county. The unions were administered by elected boards of guardians, and formed the basis for the registration districts created in 1837. Each union as a whole was assigned to a registration county, which therefore differed in places from the legal counties. The registration counties were used for census reporting from 1851 to 1911.[16] The unions also formed the basis for the sanitary districts created in 1872, which took on various local government functions.[17]

The county of Westmorland was formed in 1227.[18] From then until 1889 there were generally agreed to be 39 counties in England, although there were some liberties such as the Liberty of Ripon which were independent from their host counties for judicial purposes. The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 formally absorbed Wales into the kingdom of England and completed its division into 13 counties on the English model. Contemporary lists after that sometimes included Monmouthshire as a 40th English county, on account of its assizes being included in the Oxford circuit rather than one of the Welsh circuits.[19][20] The 39 historic counties were:[10]

- Bedfordshire

- Berkshire

- Buckinghamshire

- Cambridgeshire

- Cheshire

- Cornwall

- Cumberland

- Derbyshire

- Devon

- Dorset

- Durham

- Essex

- Gloucestershire

- Hampshire

- Herefordshire

- Hertfordshire

- Huntingdonshire

- Kent

- Lancashire

- Leicestershire

- Lincolnshire

- Middlesex

- Norfolk

- Northamptonshire

- Northumberland

- Nottinghamshire

- Oxfordshire

- Rutland

- Shropshire

- Somerset

- Staffordshire

- Suffolk

- Surrey

- Sussex

- Warwickshire

- Westmorland

- Wiltshire

- Worcestershire

- Yorkshire

Creation of county councils

[edit]

By the late 19th century, there was increasing pressure to reform the structure of English counties; borough councils and boards of guardians were elected, but there were no elections for county-level authorities. Some urban areas had also grown across county boundaries, creating problems in how they were administered. The Local Government Act 1888 sought to address these issues. It established elected county councils, which came into being in 1889 and took over the administrative functions of the quarter sessions.[21]

Some towns and cities were considered large enough to run their own county-level services and so were made county boroughs, independent from the new county councils. Urban sanitary districts which straddled county boundaries were placed entirely in one county. A new County of London was created covering the area which had been administered by the Metropolitan Board of Works since 1856, which covered the City of London and parts of Middlesex, Surrey and Kent. In those counties where the quarter sessions had been held separately for different parts of the county, separate county councils were created for each part.[22][23]

The area controlled by a county council was termed an administrative county. The 1888 Act also adjusted the county boundaries for all other purposes, including judicial functions, sheriffs and lieutenants, to match groups of the administrative counties and county boroughs. As such, Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Suffolk and Sussex retained a single sheriff and lieutenant each, despite being split between multiple administrative counties. Yorkshire kept a single sheriff, whilst each of its ridings retained a separate lieutenant and formed their own administrative counties.[24][25] In 1890 the Isle of Wight was made an administrative county whilst remaining part of Hampshire for other purposes.[26]

Constituencies were not changed by the 1888 Act and so the parliamentary counties continued to be defined as they had been when the constituencies were last reviewed in 1885, by reference to the counties as they had then existed.[27] This led to a mismatch in some areas between the parliamentary counties and the counties as had been adjusted for all other purposes. This lasted until the constituencies were next reviewed in 1918, when they were realigned to nest within the newer versions of the counties.[28]

The 1888 Act used the term 'entire county' to refer to the wider version of the county, including any associated county boroughs or parts which had been made administrative counties.[29] The informal term 'geographical county' was also used on Ordnance Survey maps to distinguish the wider version of the county from the administrative counties.[30][31]

There were various adjustments to county boundaries after 1889. There were numerous changes following the Local Government Act 1894, which converted rural sanitary districts into rural districts and established parish councils, but said that districts and parishes were no longer allowed to straddle county boundaries. The number of county boroughs gradually increased, and boundaries were occasionally adjusted to accommodate urban areas which were developing across county boundaries. In 1931 the boundaries between Gloucestershire, Warwickshire, and Worcestershire were adjusted to transfer 26 parishes between the three counties, largely to eliminate the remaining exclaves not addressed in 1844.[32]

The functions of county councils gradually grew. Notable expansions in their responsibilities included taking over education from the abolished school boards in 1902,[33] and taking over the assistance of the poor from the abolished boards of guardians in 1930.[34]

Reforms

[edit]

A Local Government Boundary Commission was set up in 1945 which reviewed the structure of local government and recommended a significant overhaul, including extensive changes to counties and county boroughs. The commission was wound up in 1949 when the government decided not to pursue these proposals.[35]

A Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London was established in 1957 and a Local Government Commission for England in 1958 to recommend new local government structures. The major outcomes of the work of the commissions came in 1965. The County of London was abolished and was replaced by the Greater London administrative area, which also included most of the remaining part of Middlesex (which was abolished as an administrative county) and areas formerly part of Surrey, Kent, Essex and Hertfordshire. Huntingdonshire was merged with the Soke of Peterborough to form Huntingdon and Peterborough, and the original administrative county of Cambridgeshire was merged with the Isle of Ely to form Cambridgeshire and Isle of Ely.[36]

A Royal Commission on Local Government in England was set up in 1966 and produced the Redcliffe-Maud Report in 1969, which recommended the complete redrawing of local government areas in England, replacing the existing counties and districts and having most local government functions exercised by all-purpose unitary authorities. Following the change in government at the 1970 general election, the incoming Conservative administration of Edward Heath abandoned the Redcliffe-Maud proposals, having campaigned against them as part of their election manifesto.[37]

Instead, the Heath government produced the Local Government Act 1972 which reorganised local government from 1 April 1974 into a two-tier structure of counties and districts across the whole of England apart from the Isles of Scilly and Greater London (which retained its two-tier structure of the Greater London Council and London boroughs which had been introduced in 1965). The administrative counties and county boroughs were all abolished, and the lower tier of district councils was reorganised.[38][39][40]

The Heath government also reformed the judicial functions which had been organised by geographical counties; the Courts Act 1971 abolished the quarter sessions and assizes with effect from 1972.[41][d] The sheriffs and lieutenants continued to exist, but both roles had lost powers to become largely ceremonial by the time of the 1970s reforms. As such, following the loss of judicial functions in 1972, the counties' roles were the administrative functions of local government, plus the limited ceremonial roles of the sheriffs and lieutenants. As part of the reforms under the Local Government Act 1972 the post of sheriff was renamed 'high sheriff', and both they and the lieutenants were appointed to the new counties created in 1974.[43]

Whilst the administrative counties and county boroughs were abolished in 1974, the wider geographical or historic counties were not explicitly abolished by the 1972 Act, albeit they were left with no administrative or ceremonial functions.[44]

Following the 1974 reforms there were 45 counties, six of which were classed as metropolitan counties, covering the larger urban areas:

The other 39 counties were classed as non-metropolitan counties:

- Avon

- Bedfordshire

- Berkshire

- Buckinghamshire

- Cambridgeshire

- Cheshire

- Cleveland

- Cornwall

- Cumbria

- Derbyshire

- Devon

- Dorset

- Durham

- East Sussex

- Essex

- Gloucestershire

- Hampshire

- Hereford and Worcester

- Hertfordshire

- Humberside

- Isle of Wight

- Kent

- Lancashire

- Leicestershire

- Lincolnshire

- Norfolk

- North Yorkshire

- Northamptonshire

- Northumberland

- Nottinghamshire

- Oxfordshire

- Shropshire

- Somerset

- Staffordshire

- Suffolk

- Surrey

- Warwickshire

- West Sussex

- Wiltshire

Most of the non-metropolitan counties retained the names of historic counties and were defined by reference to the administrative and geographical counties which preceded them, retaining the same or similar boundaries where practicable. Whilst the Heath government had rejected the more radical Radcliffe-Maud proposals, they did still make adjustments to boundaries where they concluded they were necessary to better align with functional economic areas. For example, the north-western part of Berkshire was transferred to Oxfordshire on account of being separated from the rest of Berkshire by the Berkshire Downs hills and having better connections to the city of Oxford than to Berkshire's largest town and administrative centre of Reading. Similarly, Gatwick Airport was transferred from Surrey to West Sussex so that it could be in the same county as Crawley, the adjoining new town.[45][46][47]

Four of the non-metropolitan counties established in 1974 were given names that had not previously been used for counties: Avon, Cleveland, Cumbria, and Humberside. Another was a merger of two former counties and combined both their names: Hereford and Worcester. The pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Rutland, Westmorland, and Huntingdon and Peterborough were considered too small to function efficiently as separate counties, and did not have their names taken forward by new counties. Cumberland and Westmorland were both incorporated into Cumbria (alongside parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire). Huntingdon and Peterborough became lower-tier districts within Cambridgeshire, and Rutland was made a district of Leicestershire.[48]

Further changes

[edit]The metropolitan county councils were abolished in 1986 after just 12 years in operation. The Greater London Council was abolished at the same time. The metropolitan counties and Greater London continued to legally exist as geographic areas and retained their high sheriffs and lieutenants despite the loss of their upper-tier councils. The lower-tier metropolitan boroughs and London boroughs took on the functions of the abolished councils, with some functions (such as emergency services, civil defence and public transport) being delivered through joint committees.[49]

Further reform in the 1990s allowed the creation of non-metropolitan counties containing a single district, where one council performed both county and district functions. These became informally known as unitary authorities.[50] The first was the Isle of Wight, where the two districts were abolished and the county council took over their functions in 1995.[51]

In 1996, Avon, Cleveland and Humberside were abolished after just 22 years in existence. None of those three had attracted much public loyalty, and there had been campaigns to abolish them, especially in the case of Humberside.[52] Those three counties were split into unitary authorities, each of which was legally a new non-metropolitan county and a district covering the same area, with the district council also performing county functions. Rather than appoint lieutenants and high sheriffs for these new counties created in 1996, it was decided to resurrect the pre-1974 practice of defining counties for the purposes of lieutenancy and shrievalty separately from the local government counties.[53][54]

Several other unitary authorities were created between 1996 and 1998. Many of these were districts based on larger towns and cities, including several places that had been county boroughs prior to 1974. Being made unitary authorities therefore effectively restored the pre-1974 powers in such cases. Whilst these unitary authorities are legally all non-metropolitan counties, they are rarely referred to as counties other than in the context of local government law.

The pre-1974 counties of Rutland, Herefordshire and Worcestershire also regained their independence. Rutland was made a unitary authority in 1997,[55] and in 1998 Herefordshire was made a unitary authority and Worcestershire was re-established as a two-tier county.[56] Berkshire County Council was abolished in 1998 and the county's six districts became unitary authorities, but unusually the non-metropolitan county of Berkshire was not abolished. The six Berkshire unitary authorities are the only ones not to also be non-metropolitan counties.[57]

Further reforms in 2009 and between 2019 and 2023 saw more unitary authorities created within the non-metropolitan counties. Since the most recent changes in 2023, England outside Greater London and the Isles of Scilly has been divided into 84 metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties for local government purposes. The 48 ceremonial counties used for the purposes of lieutenancy have been unchanged since 1998.

Local government

[edit]

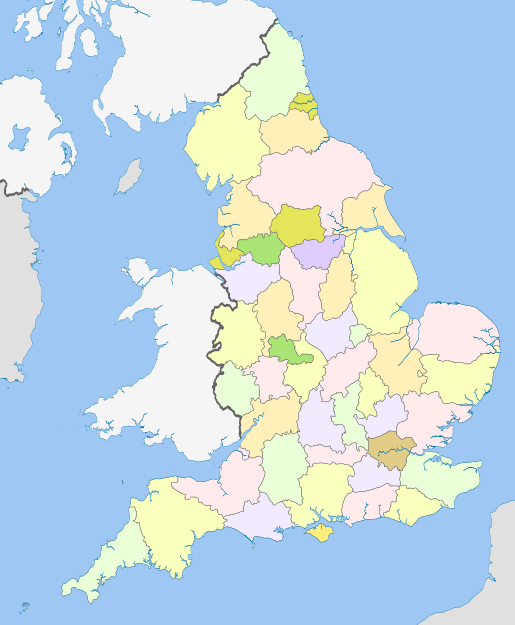

Since the latest changes in 2023 there have been 84 counties for local government purposes, which are categorised as metropolitan or non-metropolitan counties. The non-metropolitan counties may governed by one or two tiers of councils. Those which are governed by one tier (unitary authorities) may either be governed by a county council which also performs the functions of a district, or a district council which also performs the functions of a county. The effect is the same, with only marginal differences in terminology; district councils are elected by wards, county councils by electoral divisions. The local government counties are listed below, with the numbers corresponding to the adjoining map.[58]

Metropolitan counties

[edit]There have been no county councils since 1986; these are governed by the metropolitan borough councils with some joint committees. Most now form part or all of a combined authority.

- Greater Manchester (27)

- Merseyside (28)

- South Yorkshire (24)

- Tyne and Wear (2)

- West Midlands (37)

- West Yorkshire (9)

Non-metropolitan counties

[edit]- Two tiers

Upper-tier county council and multiple lower-tier district councils:

- Cambridgeshire (45)

- Derbyshire (25)

- Devon (81)

- East Sussex (70)

- Essex (48)

- Gloucestershire (58)

- Hampshire (74)

- Hertfordshire (51)

- Kent (69)

- Lancashire (6)

- Leicestershire (39)

- Lincolnshire (21)

- Norfolk (46)

- Nottinghamshire (22)

- Oxfordshire (57)

- Staffordshire (35)

- Suffolk (47)

- Surrey (73)

- Warwickshire (38)

- West Sussex (72)

- Worcestershire (59)

- One tier

County council serving as unitary authority:

- Cornwall (84)

- Durham (3)

- Isle of Wight (77)

- North Yorkshire (10)

- Northumberland (1)

- Shropshire (33)

- Somerset (80)

- Wiltshire (65)

District council serving as unitary authority:

- Bath and North East Somerset (64)

- Bedford (52)

- Blackburn with Darwen (8)

- Blackpool (7)

- Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (79)

- Brighton and Hove (71)

- Bristol (62)

- Buckinghamshire (56)

- Central Bedfordshire (53)

- Cheshire East (32)

- Cheshire West and Chester (31)

- Cumberland (5)

- Darlington (11)

- Derby (26)

- Dorset (78)

- East Riding of Yorkshire (17)

- Halton (29)

- Hartlepool (14)

- Herefordshire (60)

- Kingston upon Hull (18)

- Leicester (40)

- Luton (54)

- Medway (68)

- Middlesbrough (13)

- Milton Keynes (55)

- North East Lincolnshire (20)

- North Lincolnshire (19)

- North Northamptonshire (43)

- North Somerset (63)

- Nottingham (23)

- Peterborough (44)

- Plymouth (83)

- Portsmouth (76)

- Redcar and Cleveland (15)

- Rutland (41)

- South Gloucestershire (61)

- Southampton (75)

- Southend-on-Sea (49)

- Stockton-on-Tees (12)

- Stoke-on-Trent (36)

- Swindon (66)

- Telford and Wrekin (34)

- Thurrock (50)

- Torbay (82)

- Warrington (30)

- West Northamptonshire (42)

- Westmorland and Furness (4)

- York (16)

No county council but multiple districts serving as unitary authorities:

- Berkshire (67) (unitary districts being Bracknell Forest, Reading, Slough, West Berkshire, Windsor and Maidenhead, and Wokingham)

Exceptions

[edit]Greater London and the Isles of Scilly do not form part of any county for the purposes of local government legislation.

- Greater London

Greater London was created in 1965 by the London Government Act 1963 as a sui generis administrative area, with the Greater London Council functioning as an upper-tier authority.[59] It consists of the City of London plus 32 London boroughs. It was left unaltered by the 1972 Act. The Greater London Council was abolished along with the metropolitan county councils in 1986.[49]

Since 2000, Greater London has had an elected Assembly and Mayor responsible for strategic local government.[60] Whilst not a county in terms of local government legislation, Greater London is deemed to comprise two counties for the purposes of lieutenancy: the City of London (covering the 'square mile' at the centre of the conurbation) and a Greater London lieutenancy county covering the rest of the area, being the 32 London boroughs.[54]

- Isles of Scilly

The Council of the Isles of Scilly was formed in 1890 as a sui generis district council. It was given the "powers, duties and liabilities" of a county council in 1930.[61] Some functions, such as health and economic development, are shared with Cornwall Council. For lieutenancy purposes the islands form part of the ceremonial county of Cornwall.[43]

Ceremonial counties

[edit]From 1974 to 1996 the local government counties were also used for the purposes of lieutenancy, with the exceptions that the Isles of Scilly were deemed part of Cornwall for lieutenancy purposes,[43] and Greater London was deemed to be two lieutenancy counties (the City of London and the rest of Greater London) under the Administration of Justice Act 1964.[62]

As unitary authorities began to be created in the mid 1990s it was decided to define counties for the purposes of lieutenancy differently from the local government counties in some cases. This was effectively reverting to the pre-1974 approach, when lieutenancy areas had covered multiple county boroughs and administrative counties. Regulations came into effect in 1996 introducing a new definition of the counties for lieutenancy purposes, being either the local government counties or specified groups of them. On the abolition of Avon, Cleveland and Humberside in 1996 the regulations split the area of Avon for the purposes of lieutenancy between Gloucestershire, Somerset and Bristol (a change from the pre-1974 position when Bristol had been part of the Gloucestershire lieutenancy). Cleveland was split between North Yorkshire and County Durham, and Humberside was split between Lincolnshire and a new 'East Riding of Yorkshire' lieutenancy county.[53]

The regulations were then consolidated into the Lieutenancies Act 1997. When Herefordshire, Rutland and Worcestershire were re-established as local government counties in 1997 and 1998 no amendment was made to the 1997 Act regarding them, allowing them to also serve as their own lieutenancy areas.[56][55] The lieutenancy counties have not changed in area since 1998, although the definitions of which local government counties are included in each lieutenancy have been amended to reflect new unitary authorities being created since 1997.[54]

In legislation the lieutenancy areas are described as 'counties for the purposes of the lieutenancies'; the informal term 'ceremonial county' has come into usage for such areas, appearing in parliamentary debates as early as 1996.[63] Since the adoption of different definitions of the counties for local government and lieutenancy purposes in 1996 there have been a growing number of instances where a local government county shares a name with a larger ceremonial county. For example the local government (non-metropolitan) county of Gloucestershire is the area administered by Gloucestershire County Council, but the ceremonial county of Gloucestershire additionally includes the unitary authority of South Gloucestershire.[53]

The ceremonial counties and their definitions by reference to local government areas (metropolitan counties, non-metropolitan counties, Greater London and the Isles of Scilly) are as follows:[54]

Largest settlements and county towns

[edit]Culture

[edit]

There is no well-established series of official symbols or flags covering all the counties. From 1889 the newly created county councils could apply to the College of Arms for coats of arms, often incorporating traditional symbols associated with the county. This practice continued as new county councils were created in 1965 and 1974. Such armorial bearings were granted to the council rather than the geographic area of the counties themselves. Some have therefore become obsolete if the council they were granted to no longer exists. A recent series of flags, with varying levels of official adoption, have been established in many of the counties by competition or public poll. County days are a recent innovation in some areas.[64][65]

There are 17 first-class men's county cricket teams that are based on historical English counties. These compete in the County Championship and in the other top-level domestic competitions organised by the England and Wales Cricket Board along with the 18th first-class cricket county - Glamorgan in Wales. There are also 19 English minor county teams which, along with a Wales Minor Counties side, compete for the Minor Counties Championship.[66]

The County Football Associations are roughly based on English counties, with exceptions such as the combinations of Berkshire and Buckinghamshire and Leicestershire and Rutland.[67]

Postal counties

[edit]The Royal Mail has always required postal addresses to include the name of certain towns, known as post towns, to assist with efficiently directing the mail.[68] Historically they also required the name of the county in which that post town lay to be included as part of the address. There was also a series of official county name abbreviations sanctioned for postal use. For many rural areas and villages the post town to which they were assigned lay in a different county, and so in many places a correct postal address included the name of a county where the specific address was not located. For example the village of Easton on the Hill in Northamptonshire had to include Stamford, Lincolnshire in its address. The postal counties therefore included the same set of towns as the geographical counties, but had quite different boundaries.[69]

The Royal Mail was unable to follow the changes to county boundaries in 1965 and 1974 due to cost constraints and because several new counties had names that were too similar to post towns. The main differences were that Hereford and Worcester, Greater Manchester and Greater London could not be adopted as postal counties and that Humberside had to be split into North Humberside and South Humberside.[70]

The use of postal counties was abandoned by the Royal Mail in 1996 after postcodes had become sufficiently well-established.

See also

[edit]- List of English counties

- List of ceremonial counties of England by population

- List of two-tier counties of England by population

- List of county councils in England

- List of historic counties of England

- Toponymical list of English counties

- List of the most populated settlements by county

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The metropolitan county councils were abolished in 1986 and their powers transferred to the metropolitan boroughs, but the counties themselves were not abolished. Unitary authorities hold the status of a combined non-metropolitan county and district. The exception is Berkshire where the county council was abolished and its powers transferred to new unitary authorities, but its districts were not granted the status of non-metropolitan counties, thus retaining the Royal County of Berkshire. Greater London was designated an 'administrative area' rather than a county under the London Government Act 1963, although it does contain the two ceremonial counties of Greater London and the City of London.

- ^ With the exception of the non-metropolitan county of Stockton-on-Tees, which straddles the two ceremonial counties of County Durham and North Yorkshire.

- ^ The charter of Henry I which gave London the right to appoint its own sheriffs is undated, but the evidence suggests it was issued between 1130 and 1133, with sometime around Easter 1132 considered the most likely date.[8]

- ^ Despite the name, county courts were not arranged by counties but by separately defined county court districts.[42]

- ^ Like most unitary authorities, Durham is legally a non-metropolitan county and a district covering the same area, with just one council. Unusually, they have different names; the county is just called 'Durham' but the district is called 'County Durham' (which is how the area is often described in everyday language, to distinguish it from the city of Durham). There is no district council, with Durham County Council serving as unitary authority. The ceremonial county is also legally just called 'Durham'.

References

[edit]- ^ "A Beginners Guide to UK Geography (2023)". Open Geography Portal. Office for National Statistics. 24 August 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Aspects of Britain: Local Government. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1996.

- ^ Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice Potter (1906). English local government, from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations Act. London: Longmans, Green. pp. 287, 310–318. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Records of the Palatine of Durham". The National Archives. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Landau, Norma (2023). The Justices of the Peace 1679–1760. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780520312340. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic (1991). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England: Volume II. London: Royal Historical Society. p. xvi. ISBN 0861931270.

- ^ Anson, William R. (1892). The Law and Custom of the Constitution: Part 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 236. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Tatlock, J. S. P. (October 1936). "The Date of Henry I's Charter to London". Speculum. 11 (4): 461–469. doi:10.2307/2848538. JSTOR 2848538. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice Potter (1906). English local government, from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations Act. London: Longmans, Green. pp. 284–286. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Milita Act 1796 (37 Geo. 3 c. 3)". The Statutes at Large. M. Baskett. 1798. p. 426. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Militia Act. Sweet & Maxwell. 1882. p. 21. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Parliamentary Boundaries Act. 1832. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 6. London: Victoria County History. 1959. pp. 324–333. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Fletcher, David (1999). "The Ordnance Survey's Nineteenth Century Boundary Survey: Context, Characteristics and Impact". Imago Mundi. 51: 131–146. doi:10.1080/03085699908592906. JSTOR 1151445. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1844 c. 61, retrieved 18 March 2024

- ^ "Poor Law / Registration County". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Guardians as Rural Sanitary Authorities: Powers and Duties under Public Health Act, 1872, and Sewage Utilization Acts. London: Knight & Co. 1872. p. 2. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic (1991). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England: Volume 2. London: Royal Historical Society. p. 756. ISBN 0861931270.

- ^ Cockburn, J. S. (1972). A History of English Assizes, 1558–1714. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0521084490. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice Potter (1906). English local government, from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations Act. p. 310. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ B. Keith-Lucas, Government of the County in England, The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (March 1956), pp. 44-55.

- ^ Thomson, D. (1978). England in the Nineteenth Century (1815–1914).

- ^ Pulling, Alexander (1889). A Handbook for County Authorities. W. Clowes and Sons. p. 3. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Bryne, T. (1994). Local Government in Britain.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1888", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1888 c. 41 Section 59

- ^ "Local Government Board's Provisional Order Confirmation (No. 2) Act 1889". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Stanford's Parliamentary County Atlas. London: Edward Stanford. 1885. p. 22. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Representation of the People Act 1918", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1918 c. 64, retrieved 18 March 2024

- ^ Section 100

- ^ "Administrative Areas Series". Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Harley, John Brian (1975). Ordnance Survey Maps: A descriptive manual. Ordnance Survey. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-319-00000-7. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Provisional Order Confirmation (Gloucestershire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire) Act

- ^ "Education Act 1902". Education in the UK. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1929", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1929 c. 17, retrieved 18 March 2024

- ^ Hansard, House of Commons 5th series, vol 463, col 74.

- ^ "Local Government (East Midlands) HC Deb 09 March 1964 vol 691 cc170-211". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 9 March 1964. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ "1970 Conservative Party Manifesto". conservativemanifesto.com. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Kingdom, John (1991). Government and Politics in Britain.

- ^ Redcliffe-Maud & Wood, B. (1974). English Local Government Reformed.

- ^ Sandford, Mark (26 October 2022). "Long shadows: 50 years of the Local Government Act 1972". House of Commons Library. UK Parliament. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Courts Act 1971", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1971 c. 23, retrieved 18 March 2024

- ^ Udall, Henry (1846). The New County Courts Act. London: V. and R. Stevens, and G. S. Norton. p. 3. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Local Government Act 1972: Section 216", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1972 c. 70 (s. 216), retrieved 18 March 2024

- ^ "Celebrating the historic counties of England". Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Hampton, W. (1991). Local Government and Urban Politics.

- ^ Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (1 October 2013). "England's traditional counties". HM Government. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ^ "Current and historic counties". Department for Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "The English Non-metropolitan Districts (Names) Order 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1973/551, retrieved 19 March 2024

- ^ a b "Local Government Act 1985", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1985 c. 51, retrieved 20 March 2024

- ^ Jones, Bill; Kavanagh, Dennis; Moran, Michael; Norton, Philip (2004). Politics UK (5th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 0582423333.

- ^ "The Isle of Wight (Structural Change) Order 1994", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1994/1210

- ^ "Local Government Reorganisation (Humberside), 26 May 1994". Hansard. UK Parliament. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Local Government Changes for England (Miscellaneous Provision) Regulations 1995", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1995/1748, retrieved 6 March 2024

- ^ a b c d "Lieutenancies Act 1997", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1997 c. 23, retrieved 20 March 2024

- ^ a b "The Leicestershire (City of Leicester and District of Rutland) (Structural Change) Order 1996", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1996/507, retrieved 20 March 2024

- ^ a b "The Hereford and Worcester (Structural, Boundary and Electoral Changes) Order 1996", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1996/1867, retrieved 20 March 2024

- ^ "The Berkshire (Structural Change) Order 1996", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1996/1879, retrieved 20 March 2024

- ^ "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Bryne, T., Local Government in Britain (1994)

- ^ "Greater London Authority Act 1999", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1999 c. 29, retrieved 21 March 2024

- ^ "Isles of Scilly Order 1930". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Administration of Justice Act 1964", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1964 c. 42, retrieved 21 March 2024

- ^ "Leicestershire (City of Leicester and District of Rutland) (Structural Change) Order 1996: House of Lords debate 28 February 1996". Hansard. UK Parliament. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "County flags to fly at Department for Communities and Local Government". gov.uk. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Ockso, Glen (13 May 2015). "So long, Eric Pickles, and thanks for all the flags". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "County Championship". England and Wales Cricket Board. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "The County Football Associations". The Football Association. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Postcode Address File Code of Practice" (PDF). Royal Mail. May 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Foster, Thelma J. (1996). Secretarial Procedures. Nelson Thornes. p. 233. ISBN 9780748727919. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Local Government in England and Wales: A guide to the new system. Department of the Environment. 1974. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-11-750847-7. Retrieved 21 March 2024.